Investing in research potential in Belgium

Since 2016, therefore, in addition to the large sums it devotes each year to basic research, the Foundation has decided to allocate a doctoral research grant every other year to young researchers (up to the age of 30) working in Belgium. Besides a financial grant of 200,000 euros over a 4-year period, the recipient benefits from top-quality supervision within a renowned research team. The recipient of this year’s second edition, Lies Van Horebeek (KUL Leuven24), was officially awarded the doctoral grant on 16 October 2018 in the course of an academic session.

Lies Van Horebeek (24) is a bioengineer whose research project proposes a wholly new explanation. For a long time, it was assumed that the genetic code of all our body cells is identical. It is now becoming increasingly clear that in fact our bodies are mosaics of cells, the genetic codes of which vary slightly from cell to cell. These differences were not inherited from our parents, but appeared in some of our cells over the course of our lives. They are known as “somatic variants”. Researchers have recently observed that such variants contribute to the apparition of conditions such as autoimmune and neurological diseases. In her master’s thesis in the biomedical sciences, Lies Van Horebeek developed a method which enables somatic variants to be detected in the immune-system cells of MS patients.The Belgian Charcot Foundation doctoral grant will enable Lies Van Horebeek to determine whether and how such somatic variants play a role in the apparition or progression of MS. She will also be able to verify whether these variants can be used as markers of the immune cells which contribute to the apparition of MS. Such markers could be used to monitor a patient’s response to a treatment.

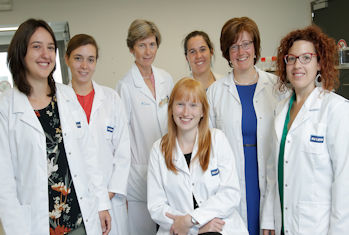

Van links naar rechts: Marijne Vandebergh, Klara Mallants, Prof. Bénédicte Dubois, Ide Smets, Prof. An Goris, Dr. Emanuela Oldoni en in het midden Lies Van Horebeek (Laureaat van de Charcot Fellowship 2018-2022) - © KU Leuven | Rob Stevens

Van links naar rechts: Marijne Vandebergh, Klara Mallants, Prof. Bénédicte Dubois, Ide Smets, Prof. An Goris, Dr. Emanuela Oldoni en in het midden Lies Van Horebeek (Laureaat van de Charcot Fellowship 2018-2022) - © KU Leuven | Rob Stevens

The Laboratory for Neuroimmunology focusses on translational research on multiple sclerosis (MS). "This means that we start from important questions faced in the clinic, and investigate these in the lab in order to translate the results back to improved care for patients with MS", explains Prof A. Goris. For this purpose, the laboratory has a translational structure, building on the research expertise of the promoter (Prof. An Goris) and the clinical expertise of the co-promoter (Prof. Bénédicte Dubois). Both promoters have worked successfully together for more than 15 years and will together guide Lies Van Horebeek towards the successful completion of her research project. The research group has built up an extensive international collaborative network, which offers Lies the opportunity to exchange on her research with other scientists throughout the world.

Together with international colleagues, the research group demonstrated that 211 genetic risk factors influence an individual’s susceptibility to MS. With the support of the Charcot Foundation, the research group has been a pioneer in moving beyond susceptibility towards explaining the important patient-to-patient heterogeneity in MS. . Lies will now build upon this research. In particular, she will address the next key questions: what triggers whether an individual with a certain load of known genetic risk factors does or does not get MS and what determines how the disease will evolve? Lies proposes a novel explanation for the unexplained variance in MS risk between individuals, and hypothesizes that mutations that are not inherited from the parents but have arisen newly in a subset of cells of the patient (somatic mutations) play an important role.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the commonest neurological disease in young adults and affects around 13,500 people in Belgium. It may cause physical and cognitive impairment which play a crucial part in the patients’ personal and professional development. To this day, the mechanisms of MS are not yet fully known.

The research team of her supervisor Professor A. Goris has already demonstrated that susceptibility to MS depends on over 200 genetic factors. This discovery has been one of the great steps forward of the past 10 years, and has evidenced the importance of the role played by the immune-system cells in the apparition of the disease. However, these genetic factors certainly do not constitute the only explanation. Rather, the crucial question is: why does a person with a particular predisposition due to hereditary genetic factors develop the disease at all?

Lies Van Horebeek proposes a novel explanation in her research project. For a long time, it has been assumed that our genetic code is identical in all cells of our body. We are now starting to understand that our body actually is a mosaic of cells, which can differ slightly in their genetic material. These genetic differences are not inherited from our parents but have arisen newly in a subset of our cells, and are called somatic variants. The role of these genetic variants in the susceptibility to autoimmune and neurological diseases is increasingly being uncovered. In her Master’s thesis Biomedical Sciences, Lies has developed a method to detect such somatic variants in the immune cells of MS patients.

For my eight birthday, I asked my parents for an electricity science kit. I wanted to do experiments and learn stuff. Now, sixteen years later, nothing much has changed, as I still want to figure out how things work. However, while growing up, my interests shifted from what was around me to the mechanisms of the human body. During my five years studying Biomedical Sciences at KU Leuven, I developed a great interest for genetics. How wonderful is the ability to deposit all information the human body needs into the human genome by using only four different nucleotides! Sadly, this system is not perfect and while this is the basis that allows evolution, small deviations from the ‘normal’ genetic code can be sufficient to lead to diseases or increase the risk for disease. Many of the underlying mechanisms are still mysteries to be unravelled.

For my eight birthday, I asked my parents for an electricity science kit. I wanted to do experiments and learn stuff. Now, sixteen years later, nothing much has changed, as I still want to figure out how things work. However, while growing up, my interests shifted from what was around me to the mechanisms of the human body. During my five years studying Biomedical Sciences at KU Leuven, I developed a great interest for genetics. How wonderful is the ability to deposit all information the human body needs into the human genome by using only four different nucleotides! Sadly, this system is not perfect and while this is the basis that allows evolution, small deviations from the ‘normal’ genetic code can be sufficient to lead to diseases or increase the risk for disease. Many of the underlying mechanisms are still mysteries to be unravelled.

I discovered a passion for bioinformatics at the same time. Bioinformatics is a field in which many realisations have already been accomplished, but there is still much more progress to be made. Large amounts of data can be generated by newly developed techniques, but the difficulty remains to extract all the information hidden in this data. This challenge is also present in my PhD project and is one that I am happy to accept. Lies Van Hoorebeek