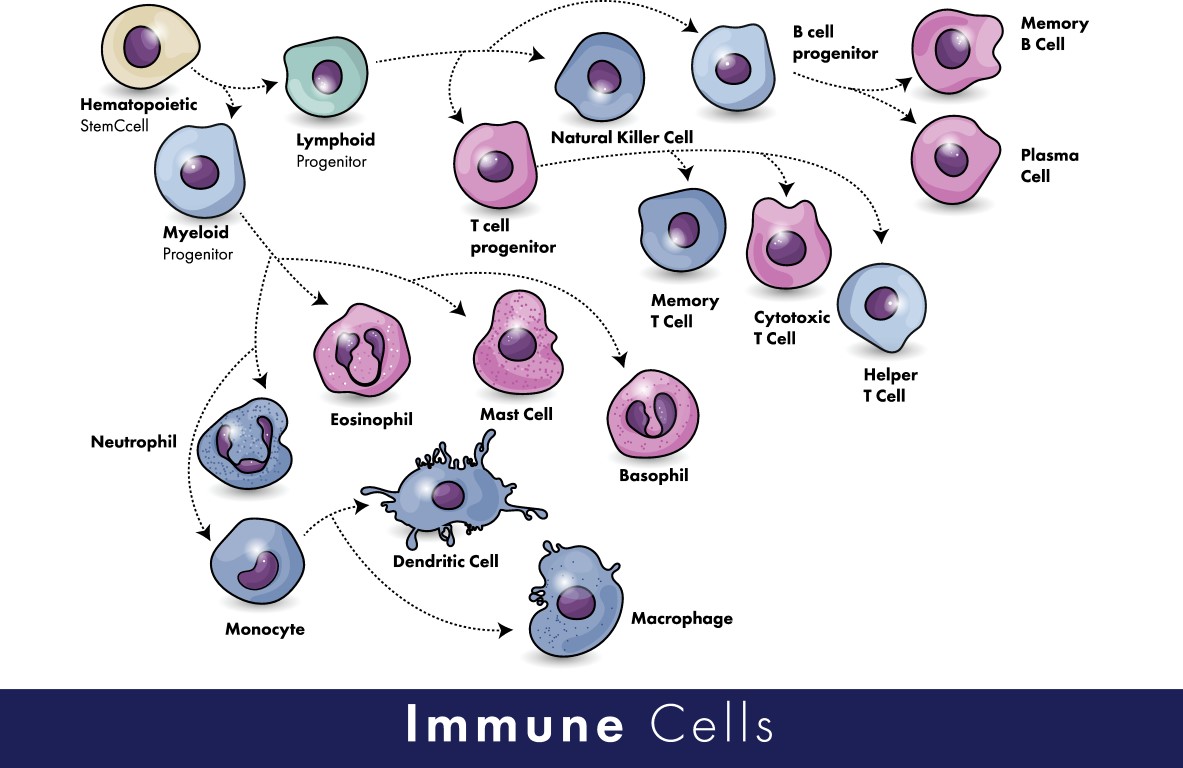

Recent technological advances have taught us that the immune system is even more complicated than we ever conceived it to be. Fifteen years ago, at the start of my career, we believed that T cells (a type of white blood cell) were the main culprit in MS, and that they were either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory. Now, we understand that even within the T cell population, tens if not hundreds of subsets and states exist. We now also know that one T cell can produce both pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules, making it even more complex. If you now also take into consideration that other immune cell types (e.g. B cells, NK cells, neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, …) have all been shown to be involved in MS, it almost becomes an inaccessible jungle.

Luckily, our scientific and therapeutic tools have evolved as well. At this moment, we can look in unprecedented depth at one person’s immune system, even at the level of a single cell. In addition, we can look at interactions between all those different immune cells, and begin to understand their ways of communication. Also, recent successes in cell-targeting therapies, such as B-cell depleting antibodies, have taught us a lot about the immunology of MS.

However, despite the success of current therapies, most of them do not work in all persons with MS, and they are still unable to prevent progression of the disease. This could have several reasons. First, the currently approved therapies do not induce repair of the damaged brain, and as people age, the brain’s inherent capacity to repair itself becomes impaired. Therefore, the damage that has been done to the brain cannot be restored anymore. Second, researchers have identified “silent progression”, also termed “progression independent of relapse activity” (PIRA), which appears to be driven by ongoing damage to brain cells in the gray matter. Finally, the existing therapies do not restore immune tolerance, meaning that the triggering event is not dealt with.

Tregs are also able to induce tissue repair, and more importantly, repair of myelin in the brain

In recent years, cell therapy has gained increased attention in the medical field. For example, CAR-T cell therapy makes use of a patient’s own T cells, which are genetically modified in the lab and then given back to the patient. This type of therapy is now approved for B-cell lymphoma and is under investigation for several other types of cancer. In the field of autoimmunity, researchers have been looking at so-called “regulatory T cells” (Tregs) as a potential way out of the immunological jungle.

Tregs are inherently equipped to dampen immune responses, but they are less functional in people with MS. In recent years, researchers have discovered a novel function of Tregs. Excitingly, these cells are also able to induce tissue repair, and more importantly, repair of myelin in the brain! This finding has sparked a renewed interest in these cells, and more specifically, in the idea of using them as a cell therapy. In theory, giving functional Tregs to a person with MS would restore their immune tolerance, thereby stopping attacks to the brain, and it would support repair of damaged brain tissue. Of course, there is still a long way to go between this theoretical cure and an actual therapy. First, we need to make sure that the Tregs we give back to a patient are functional and remain so when in the body.

For example our lab has recently discovered that Tregs change and become, dysfunctional when they cross the blood-brain barier, which is the gateway to the brain. In addition, we need to consider safety, specificity and other issues. Many researchers around the world are currently investigating whether genetic modification of Tregs is feasible to tackle these issues.

In summary, recent technological and therapeutic advances have uncovered the highly complex nature of the immune system, and we are still learning about what goes wrong in people with MS. Given their inherent capacity to restore immune tolerance, and to induce tissue repair in the brain, Tregs hold great potential of providing a next-generation therapy for MS.